I think I’ve made peace with the fact that I’ll never go to Glastonbury. In the mid 90s there was a brief moment when I thought I might be able to tag along with one of my older brothers, who went every year in his bus with a big old crew. They did various ‘work’ things, and treated it like their own personal festival. I never did get a proper invite, though, perhaps because I was too square or too shy, or maybe because my brother was worried he’d have to babysit me. Some of my more adventurous school friends went, but I was never really cool enough to be included in their plans.

When I had kids, and Glastonbury became something that middle class families did, I toyed with the idea. But dragging a buggy through mud, or braving the portaloos with a toddler, or trying to get a cranky child to sleep in a tent – when what I really wanted to be doing was dancing and drugs – just didn’t appeal that much.

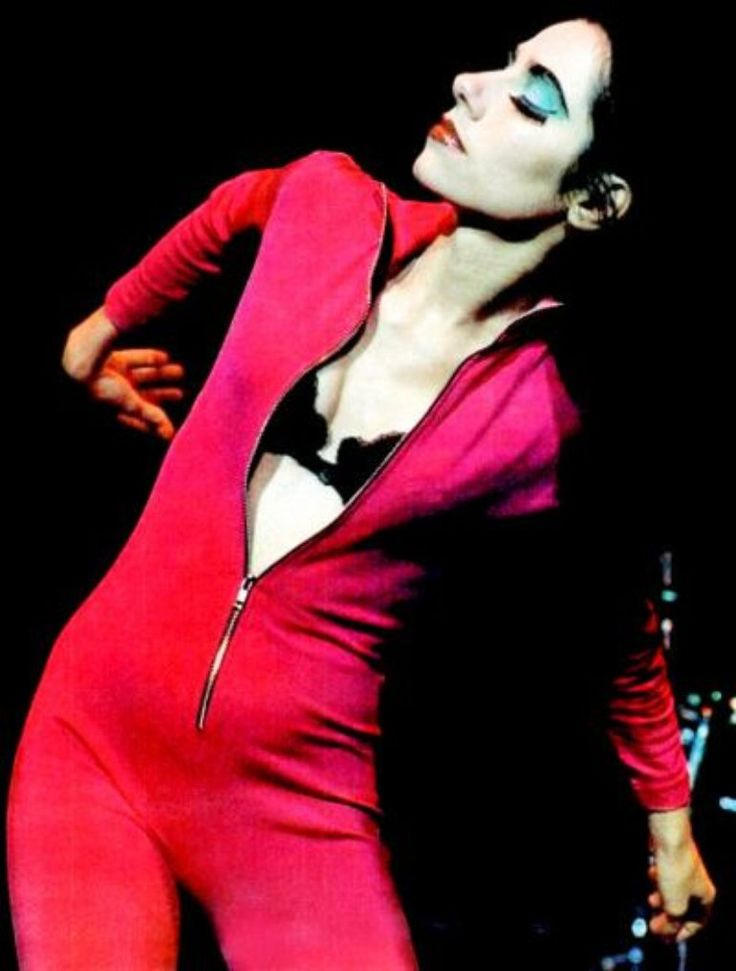

I do enjoy watching Glastonbury on the TV, though. This year I particularly loved PJ Harvey. Whether live or on screen, she is always mesmerising, and now, in her mid-fifties, her voice is better than it’s ever been. Her precision, her seriousness, her wonky smile. The way she glides through songs, stopping only to pick up an instrument, take off her coat, or introduce her band.

I’ve listened to Harvey talk about her early life, and her introduction to music; how her parents arranged music nights in local pubs and village halls, and hosted blue’s musicians in their Dorset home; how Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones once stayed for the weekend when Harvey was a young girl, and she and her brother followed him wherever he went, starstruck, silent, buzzing from his very presence.

In one interview she referred to herself as a maker, and I thought this was a curious word. And yet no-one could disagree with Harvey. She is dedicated to her music, and to creating new albums that sound different from any of her other work. She researches as if she’s delivering a government dossier. For the album The Hope Six Demolition Project, which looked at the devastation of poverty and war, she travelled to Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Washington DC. “I wanted to smell the air, feel the soil and meet the people of the countries I was fascinated with”, said Harvey.

My father is a maker, too. A jeweller, who did his apprenticeship in Hatton Garden aged 16. He’s always had a workshop with a bench, his tools, and a massive safe, that’s been relocated several times over many moves, with the help of a mini-crane. Even though my father is semi-retired he still works most days, sitting at his bench, smoking a rollie, tools all around him, precious stones in paper glistening under a lamp. He listens to football, cricket or Van Morrison, depending on mood and season. As a child, among friends whose parents were chartered accountants or pensions advisors, I was proud that my dad was a diamond dealer, because as well as making, he deals in precious stones.

My mother is a maker, too. Like me, she would tell you she is not, because the women in our family are prone to belittling their abilities. My mother doesn’t believe she has a talent for much, but the people who know her know this is bullshit. She paints. She draws. She makes everyone feel welcome. She lays a table exquisitely. She makes her home look and feel magical. Every shelf, every nook, every picture on the wall, every drawer, every folded item of clothing, every plant pot. She has a magician’s way of making everything look so right, and so beautiful. It’s a talent I try and emulate, but one I have to work very hard at, and one I can only get right 10% of the time, and in about 5% of my home.

When my mother and father owned a jewellery shop, my mother was in charge of the window displays. She would create aviaries, forests, fairgrounds, with moss, glass baubles, tiny felt animals, papier-mâché, brightly coloured ribbons, shantung silk. She would spend time finding just the right props, whether paper flowers, or perspex display boxes, or the perfect hand-painted robin to perch on a branch she’d found in the woods. When jumble sales were good, my mother would always discover the real treasure for her creations. I wish we’d taken more photographs of the displays, because although I love walking past Fortnum and Mason’s windows in summer, and Liberty windows at Christmas, rarely do I think they are better than my mother’s work.

She always invited me and my siblings to help her, which rubbed off on my sister far more than it did on me. I’m still not a confident bed-maker, and I still have to call my mother to ask her where to hang a picture, or position a chair or lamp. My sister took on her talent. She knows most of what my mother knows. But none of us know my father’s tricks. He’s never let anyone in his family into his world of making. We often wonder: how do such thick, inelegant fingers manage to make such intricate, fine jewellery? I do believe my father doesn’t know the answer to this, either.

This is a ramble. I told you it would be. But I’m worried that I’ll never be a maker. I write advertisements, that’s what I do for a living. But I take such a scattergun approach to my own writing. When people say “I use every minute of the day wisely” I wonder why I can’t. I wonder why I watch others being busy, and feel jealous, when everything they’re doing is mostly available to me. So, from this point on, I’m going to try and post something on this Substack every week. You’ll be updated on my latest embryo transfer next week. Perhaps I’ll tell you what I’ve been eating that hasn’t made me want to throw up. And perhaps I’ll be able to report back to you that the more I write, the happier I feel.

You make by watching so it’s not time wasting now is it!

Grace, you are a maker. You make words flow for starters! And when words flow you make others think, reflect and imagine. I have such vivid pictures in my head right now - of jeweller’s hands and shopfronts and beautiful corners of rooms